The food on our table

By Rex Catubig

APRIL Filipino Food Month’s celebration of our culinary heritage takes me on a gastronomic reminiscence of the food on our table in our barrio.

Barrio Calmay was a Lilliputian town, where one could buy cheap home-cooked food in little pakanan or carinderia.

Mama Bestre was undoubtedly the primus inter pares in this department. He served the best adobon baboy to my young palette’s recall. And my elder brother likes to boast that Mama Bestre’s little place was the forerunner of Starbucks. It sold hot coffee way before it became a trend. The aroma of its barako coffee triggered the cock to crow and woke up the neighborhood.

Nearby, there was cook-to-order pancit con sabaw with meaty bola bola of Mama Idor, which was perfect when April brought sudden showers.

But we hardly bought ready-cooked food. My aunt took care of our nourishment and she excelled in that. But it was my father who did the marketing for food items available only in the población.

Breakfast was usually pan de sal— crunchy outside and soft and chewy inside—baked to perfection by the barrio bakery. Eggs were soft boiled or sunny side up. Insangngil ya baaw” hankered for fried tuyo or kaling ya orang.

On the side, we had puto, binatog or binuburan, reputed to be good for the gut.

Coffee had its special niche—with ground barako beans boiled till its essence fused firmly with the water. My father liked his coffee strong before espresso was a byword. But one concoction I found weird, which he and my mother loved to gulp, was eggnog (without liquor). He said it was a healthy drink and would prod me to drink it too. I could live without it. But it fortified us through segunda almuerzo.

Lunch was pork chop, adobod toyo, adobod agamang, sarciado or rellenon labos. Pochero which consisted of baka and baboy with repolyo and patatas was Sunday fare. Tinolan manok was a between-days dish.

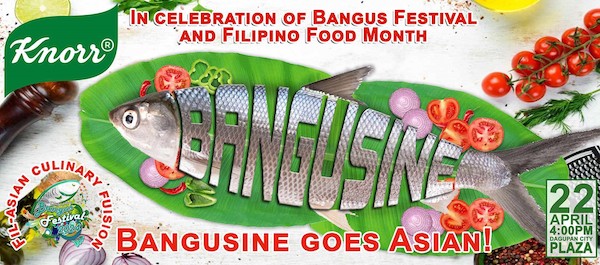

But our table was never without seafood. Bangus was sinegang ed piyas or salomague. If pinindar, marinated in vinegar, salt and garlic, and laid out on a yakayakan to dry in the sun– then fried or grilled over charcoal—since we used firewood for cooking.

Shrimps were cooked in their own liquid, or my aunt would shell them and saute them in oil and garlic. No olive oil or butter—just plain cooking oil. That was her version of gambas, unaware of the Italian pedigree. Bingalo was nothing special nor alama, as they were then affordable.

When it came to fish, my father favored pampano or Kera-keray diyos whose body on one side is dark and on the other pale, as if the flesh on that side had been eaten, hence the name that translates as “God’s leftover”. He would buy Lapu-lapu the size of bandejado only. Bigger ones were for ponsiya.

August would usher in kapen inasinan, sineret or inggis” and turned mound of steamy rice into an orangey delight.

For vegetable, pakbet, balatong, black beans, agayep, kamansi, aksiw, apayas, labong tan saluyot—whatever was freshly harvested or in season ended in a clay pot. Blanched camote tops drenched in tuka tan monamon” was a typical side.

The dessert of ripe bayawas boiled in gata with a pinch of salt was unforgettable. The aroma and flavor haunted you. But it’s a matter of acquired taste.

Before you could digest lunch, food hawkers would holler panara –fried battered crisscrossed sliced saba for merienda. The long day never ended without a litany of food.

Anyhow, our long wooden table that sat ten was generously blessed with an abundance of down-home food that our family enjoyed eating together, at times mangkamot with bare hands that let you feel the food’s texture before it’s delivered to the tongue for approval.

Fast food was unheard of. And the culinary paradise would have been better had it remained that way.