Martial Law diary

By Rex Catubig

I woke up to a stacticky radio on Saturday, September 23, 1972. No matter how I twiddled the dial, there was only hissing and crackling. And there was no newspaper, either. I was waking up to a bad dream, I thought.

I hurriedly took a jeep to the PETA office on Taft Avenue to get some news. Cecile Guidote was there. Everyone was guessing that Martial Law had been declared. We knew it was coming and the fear of the unknown gripped me.

Cecile and I hurried to her house, there waited to catch a snippet of grainy TV news: Manila Times, the leading newspaper, had been raided and closed down. Opposition leaders had been arrested and jailed.

I decided to go home to Dagupan that night thinking the situation there would be different. It was close to midnight when the last trip of Pantranco took off.

Midway down the dark highway, somewhere in Tarlac, I was roused from my catnap. Our bus was flagged down and a couple of fatigue uniformed soldiers bearing long guns boarded.

They walked up and down the narrow aisle then asked the male passengers to stand up. Reluctantly and with my heart racing, I stood up. One of the soldiers singled me out. Noticing my long hair, he barked, ” Babae ka ba?” I gulped and said feebly, “Hindi” . That was enough provocation. He produced a pair of scissors and wantonly cut my hair on one side.

The bus was quiet. Only the clipping sound of the scissors punctuated the silence. No one dared glance my way.

It was a display of power that sowed fear in everyone’s heart.

Arriving in Dagupan in the wee hours, I alighted still shaken from the surprise brush with the military.

There was the usual mise en scene at the terminal, though the place was unusually quiet. The balut vendor sat in a corner without his familiar yodel; first trip passengers stoically stood by; and the tricycle drivers simply waved to call out riders.

It was a scene out of a silent movie.

Just like in the bus, no one stared at me. I became invisible. Or the people refused to see, so as not to disturb their peace of mind.

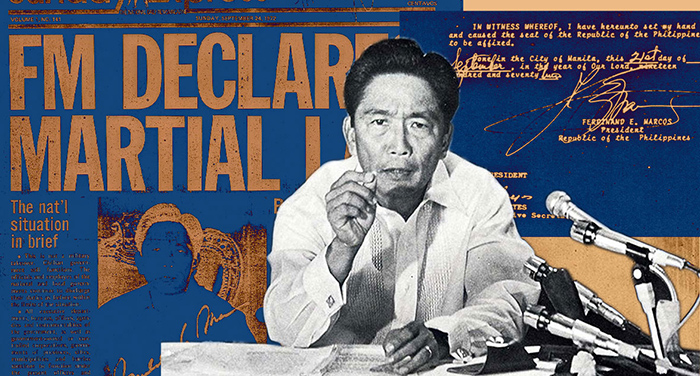

That Sunday morning, September 24, a newspaper banner headline confirmed the turn of events: “FM DECLARES MARTIAL LAW”.

It was the prelude to long days of ignominy and uncertainty. And sporadic news of random violence made sure we cowered: In a neighboring town, soldiers snipped away the mini skirt worn by a lady.

Long hair and mini-skirts were overt manifestation of non-conformity that was bane to the “New Society”. It was just the beginning.

Within a week, a high school student of my drama workshop had been picked up for mimeographing leaflets and taken to Camp Olivas in Pampanga—there to roost for the next six months in a sweltering barracks. He was sixteen.

Meanwhile, a couple of our elderly PHD women friends from the local academe were harassed by gratuitous questioning.

But these were tame compared to the unspeakable horror others suffered. The boyfriend of a college classmate was gunned down as he got off a jeep in front of UST. He was a poet a repressive regime turned into a rebel.

In one swoop, the Damocles’ sword had fallen on our heads.

But we remained alive, because with our eyes wide open, we dreamed of survival.

Revisionists may see it as some kind of Mobile Legends game.

Bearing the same ML initials, both deal with death and destruction, and a cast of heroes and villains. But Martial Law was no game. It was a nightmare that lives on.

The keloid scars on our heart and mind serve as warning and reminder.

Never again.